Build Automation

Software Process Engineering

Danilo Pianini — danilo.pianini@unibo.it

Compiled on: 2025-11-21 — printable version

Overview

- Build automation:

- The software lifecycle

- Automation styles

- Gradle as paradigmatic build automator

- Core concepts and basics

- Dependency management and configurations

- The build system as a dependency

- Hierarchial organization

- Isolation of imperativity

- Declarativity via DSLs

- Reuse via plug-ins

- Testing plug-ins

- Existing plugins

The build “life cycle”

(Not to be confused with the system development life cycle (SDLC))

The process of creating tested deployable software artifacts

from source code

May include, depending on the system specifics:

- Source code manipulation and generation

- Source code quality assurance

- Dependency management

- Compilation, linking

- Binary quality assurance

- Binary manipulation

- Test execution

- Test quality assurance (e.g., coverage)

- API documentation

- Packaging

- Delivery

- Deployment

Build automation

Automation of the build lifecycle

- In principle, the lifecycle could be executed manually

- In reality time is precious and repetition is boring

$\Rightarrow$ Create software that automates the building of some software!

- All those concerns that hold for software creation hold for build systems creation…

Build automation: basics and styles

Imperative/Custom: write a script that tells the system what to do to get from code to artifacts

- Examples: make, cmake, Apache Ant

- Abstraction gap: verbose, repetitive

- Configuration (declarative) and actionable (imperative) logics mixed together

- Highly configurable and flexible

- Difficult to adapt and port across projects

Declarative/Standard: adhere to some convention, customizing some settings

- Examples: Apache Maven, Python Poetry

- Separation between what to do and how to do it

- The build system decides how to do the stuff

- Easy to adapt and port across projects

- Configuration limited by the provided options

Hybrid automators

Create a declarative infrastructure upon an imperative basis, and allow easy access to the underlying machinery

DSLs are helpful in this context: they can “hide” imperativity without ruling it out

Still, many challenges remain open:

- How to reuse the build logic?

- within a project, and among projects

- How to structure multiple logical and interdependent parts?

Dependencies in software

nos esse quasi nanos gigantium humeris insidentes Bernard of Chartres

All modern software depends on other software!

- the operating system

- the runtime environment (e.g., the Java Virtual Machine, the Python interpreter…)

- the base libraries

- third-party libraries

- external resources (icons, sounds, application data)

All the software we build and use depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- …

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

- Which depends on other software

$\Rightarrow$ Applications have a dependency tree!

Transitive dependencies

Indirect dependencies (dependencies of dependencies) are called transitive

In non-toy projects, transitive dependencies are the majority

- It’s very easy to end up with more than 50 dependencies

Complexity quickly gets out of hand!

We need a tool that can:

- Find (for example in known archives) the libraries we need

- Download them (if found)

- Include them into a discoverable path

To do this, however, we need to know some repositories and how to refer and locate artifacts

- We need a name and a version for each library

- There is no standard, every ecosystem has its own conventions

- Some created with the programming language (e.g., Rust)

- Some evolved later with the ecosystem (Maven for Java, npm for JavaScript…)

Transitive dependency conflicts

When two libraries depend on different versions of the same library, we have a conflict

- e.g.: dependency

ArequiresBat version1, dependencyCrequiresBat version2 - How would you solve this conflict?

- Pick the latest and hope for the best?

- Pick the earliest and hope for the best?

Dependency ranges

To reduce the risk of conflicts, some systems allow specifying ranges of acceptable versions

- A range is a relaxed constraint on the version specification

Examples

- Maven (Java)

[1.2,2.0)means “from1.2(inclusive) to2.0(exclusive)”[1.2,1.3)means “from1.2(inclusive) to1.3(exclusive)”[1.2,1.3]means “from1.2(inclusive) to1.3(inclusive)”(,1.3]means “up to1.3(inclusive)”[1.2,)means “from1.2(inclusive) onwards”

- Gradle (Java, Kotlin, multiple languages)

- Same syntax as Maven, plus “rich versions”:

1.2+means “any1.2version”, i.e.,>=1.2.0 <1.3.0

- Same syntax as Maven, plus “rich versions”:

- npm / pnpm / yarn (JavaScript/TypeScript)

^1.2.3means “compatible with1.2.3”, i.e.,>=1.2.3 <2.0.0~1.2.3means “approximately1.2.3”, i.e.,>=1.2.3 <1.3.01.2.xmeans “any1.2version”, i.e.,>=1.2.0 <1.3.0

- Python (PEP 440)

>=1.2, <2.0means “from1.2(inclusive) to2.0(exclusive)”>=1.2, <1.3means “from1.2(inclusive) to1.3(exclusive)”>=1.2, <=1.3means “from1.2(inclusive) to1.3(inclusive)”<1.3means “up to1.3(exclusive)”>=1.2means “from1.2(inclusive) onwards”

Dependency ranges resolution

When multiple ranges are specified for the same dependency, the system must find a version that satisfies all constraints.

The resolver typically relies on a dependency graph:

- Input: roots (direct dependencies) with version ranges, and recursive dependencies with version ranges

- Build a graph: nodes are dependencies, edges are “depends on”

- Traverse the graph, starting from the roots (or the most constrained nodes), and reduce the ranges removing incompatible versions

- If a node ends up with an empty range, there is a conflict that cannot be resolved

- Otherwise, all nodes have non-empty ranges, pick a version for each node (typically the latest in the range)

Dependency locking

Introducing ranges leads to the explosion of the version combinations space.

- Testing all combinations is impossible!

- Different tests may resolve to different versions, leading to inconsistent results

Dependency locking is a technique to fix the versions of all dependencies (including transitive ones) to a known good set.

- The specified versions are typically ranges, in the main project manifest

- The locked versions are stored in a dedicated file

There is a trade-off between flexibility and reproducibility!

exact pins trade low maintenance risk for high ongoing cost and poor ecosystem fit:

- Libraries become uncomposable. If two libs pin different exact transitives, resolvers can’t find a common graph

- Pins don’t freeze transitives anyway. Without a lock you still get drift downstream

| Ranges, no lock | Ranges + lock | Fixed versions (exact pins) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Updates | Instant | Manual (regenerate lock file) | Manual (change version) |

| Reproducibility | Low | Maximum (transitive dependencies are locked) | High (transitive drift remains) |

| Reliability | Low (uncontrolled updates) | Medium (testing all ranges is impossible) | High (controlled updates, transitive drift) |

Dependency scopes

Dependencies may be needed in different contexts:

- Compile-time: needed to compile the code (e.g., libraries whose types are used in method signatures)

- Runtime: needed to run the code (e.g., libraries whose types are used in method bodies)

- Note: it is common for runtime dependencies to be a superset of compile-time dependencies (some dependencies are runtime-only, e.g., JDBC drivers)

- Note: even though most of the time runtime dependencies are also compile-time dependencies, this is not always the case (e.g., some components of ANTLR4…)

- Test: needed to compile and run tests (e.g., testing frameworks)

- Test runtime: needed to run tests (e.g., mocking frameworks)

- Note: similar to the runtime scope, test runtime dependencies are often a superset of test dependencies

- Build time: needed to build the code (e.g., code generators, linters, documentation tools)

- …

Scopes are typically pre-defined in declarative build systems and manually defined in imperative ones (there are exceptions to this rule).

Hybrid automators often provide pre-defined scopes and ways to define additional custom scopes.

Imperative build tool example: CMake

CMake is a widely used imperative build automation tool, especially in C and C++ projects.

- Imperative configuration: Build instructions are specified in

CMakeLists.txtusing CMake’s own scripting language. - Cross-platform: Generates native build files for various platforms (Makefiles, Visual Studio projects, etc.).

- Dependency management: Supports finding and linking against external libraries.

- Build targets: Allows defining multiple build targets (executables, libraries) within a single project.

- Custom commands: Supports custom build commands and scripts for specialized tasks.

CMake version and project name, declarative:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.0) # setting this is required

project(example_project) # this sets the project name

File globbing: search of what to build is manual/imperative:

# These instructions search the directory tree when cmake is

# invoked and put all files that match the pattern in the variables

# `sources` and `data`.

file(GLOB_RECURSE sources src/main/*.cpp src/main/*.h)

file(GLOB_RECURSE sources_test src/test/*.cpp)

file(GLOB_RECURSE data resources/*)

# You can use set(sources src/main.cpp) etc if you don't want to

# use globbing to find files automatically.

Target definitions, imperative:

# The data is just added to the executable, because in some IDEs (QtCreator)

# files are invisible when they are not explicitly part of the project.

add_executable(example ${sources} ${data})

# Just for example add some compiler flags.

target_compile_options(example PUBLIC -std=c++1y -Wall -Wfloat-conversion)

# This allows to include files relative to the root of the src directory with a <> pair

target_include_directories(example PUBLIC src/main)

# This copies all resource files in the build directory.

# We need this, because we want to work with paths relative to the executable.

file(COPY ${data} DESTINATION resources)

Depedency management, imperative:

# This defines the variables Boost_LIBRARIES that containts all library names

# that we need to link into the program.

find_package(Boost 1.36.0 COMPONENTS filesystem system REQUIRED)

target_link_libraries(example PUBLIC

${Boost_LIBRARIES}

# here you can add any library dependencies

)

Testing with googletest, imperative:

find_package(GTest)

if(GTEST_FOUND)

add_executable(unit_tests ${sources_test} ${sources})

# This define is added to prevent collision with the main.

# It might be better solved by not adding the source with the main to the

# testing target.

target_compile_definitions(unit_tests PUBLIC UNIT_TESTS)

# This allows us to use the executable as a link library, and inherit all

# linker options and library dependencies from it, by simply adding it as dependency.

set_target_properties(example PROPERTIES ENABLE_EXPORTS on)

target_link_libraries(unit_tests PUBLIC ${GTEST_BOTH_LIBRARIES} example)

target_include_directories(unit_tests PUBLIC ${GTEST_INCLUDE_DIRS})

endif()

Packaging with CPack, mostly imperative with some declarative parts:

# All install commands get the same destination. this allows us to use paths

# relative to the executable.

install(TARGETS example DESTINATION example_destination)

# This is basically a repeat of the file copy instruction that copies the

# resources in the build directory, but here we tell cmake that we want it

# in the package.

install(DIRECTORY resources DESTINATION example_destination)

# Now comes everything we need, to create a package

# there are a lot more variables you can set, and some

# you need to set for some package types, but we want to

# be minimal here.

set(CPACK_PACKAGE_NAME "MyExample")

set(CPACK_PACKAGE_VERSION "1.0.0")

# We don't want to split our program up into several incomplete pieces.

set(CPACK_MONOLITHIC_INSTALL 1)

# This must be last

include(CPack)

Declarative build tool example: Python Poetry

Poetry is a modern, declarative build and dependency management tool for Python.

- Declarative configuration: All project metadata, dependencies, and build instructions are specified in

pyproject.toml.- Declarative build tools tend to favor markup files over scripts:

- XML (Maven)

- TOML (Poetry, Rust’s Cargo)

- JSON (Node.js’s npm)

- YAML (JetBrains’ Amper)

- Declarative build tools tend to favor markup files over scripts:

- Scripted tasks: Allows definition of custom scripts for automation.

- Dependency resolution: Handles dependency resolution and locking via

poetry.lock. - Virtual environments: Automatically manages isolated Python environments per project.

- Build and publish: Supports building and publishing packages to PyPI or other repositories.

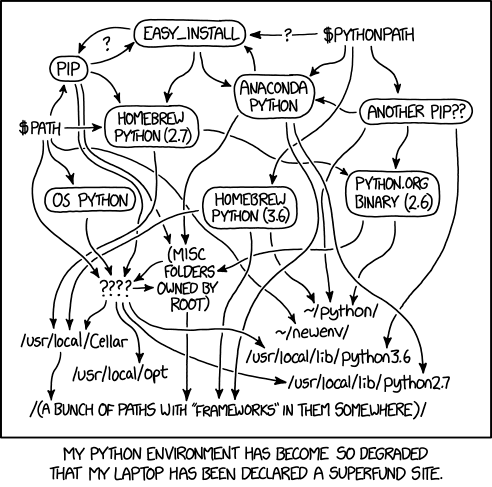

Python’s conflicting standards

Since there were no standard management systems originally, multiple tools proliferated

Python ecosystem

-

By default, Python is installed system-wide

- i.e. there should be one (and only one) Python interpreter on the system

- Problem 1: two different projects cannot use different versions of Python!

-

All Python installations come with

pip, the package installer for Python- Python packages are supposed to be installed system-wide with

pip install PACKAGE_NAME - Problem 2: Two different projects cannot use different versions of the same package!

- Python packages are supposed to be installed system-wide with

-

PyEnvis a tool to manage multiple Python installations on the same system- tackles Problem 1

- Poetry checks that the right Python version is used, but does not manage Python installations

-

virtualenvandvenvcreate virtual Python installations on the same systemvirtualenvis a third-party tool,venvis built-in in Python 3.3 and later- tackles Problem 2

- Poetry automatically creates and manages virtual environments for each project

Poetry’s canonical project structure

root-directory/

├── main_package/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── sub_module.py

│ └── sub_package/

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── sub_sub_module.py

├── test/

│ ├── test_something.py

│ └── test_something_else.py/

├── pyproject.toml # File where project configuration (metadata, dependencies, etc.) is stored

├── poetry.toml # File where Poetry configuration is stored

├── poetry.lock # File where Poetry locks the dependencies

└── README.md

If you already use Python, notice:

- no

requirements.txtnorrequirements-dev.txt pyproject.toml,poetry.toml, andpoetry.lockare Poetry-specificpoetry.lockis generated automatically by Poetry, and should not be edited manually

A Python calculator

(courtesy of Giovanni Ciatto)

[tool.poetry]

# publication metadata

name = "unibo-dtm-se-calculator"

packages = [ # files to be included for publication

{ include = "calculator" },

]

version = "0.1.1"

description = "A simple calculator toolkit written in Python, with several UIs."

authors = ["Giovanni Ciatto <giovanni.ciatto@unibo.it>"]

license = "Apache 2.0"

readme = "README.md"

# dependencies (notice that Python is considered a dependency)

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = "^3.10.0"

Kivy = "^2.3.0"

# development dependencies

[tool.poetry.group.dev.dependencies]

poetry = "^1.7.0"

pytest = "^8.1.0"

coverage = "^7.4.0"

mypy = "^1.9.0"

# executable commands that will be created then installing this package

[tool.poetry.scripts]

calculator-gui = "calculator.ui.gui:start_app"

calculator = "calculator.ui.cli:start_app"

# where to download the dependencies from

[[tool.poetry.source]]

name = "PyPI"

priority = "primary"

# packaging dependencies

[build-system]

requires = ["poetry-core"]

build-backend = "poetry.core.masonry.api"

# the project-specific environment will be created in the local .venv folder

[virtualenvs]

in-project = true

Pure TOML: completely declarative

Poetry: build lifecycle

Poetry is used via the poetry command line tool:

poetry install– resolves and installs dependenciespoetry run <command>– runs a command within the virtual environment

Actual behavior of poetry install

- Validate the project is correct and all necessary information is available

- Verify the version of Python is correct

- Resolve the dependencies, or use the ones in

poetry.lockif already available - Retrieve the dependencies from the specified sources

- Create a virtual environment if not already available

- Install the dependencies in the virtual environment

Subsequent lifecycle phases are managed by the poetry run command, and are thus custom.

❗ Except for install, Poetry does not provide a predefined lifecycle

A structured build lifecycle: Apache Maven

A build lifecycle typical of declarative automators, composed by phases.

⚠️ Selecting a phase implies executing all previous phases.

validate– validate the project is correct and all necessary information is availablecompile– compile the source code of the projecttest– test the compiled source code using a suitable unit testing framework. These tests should not require the code be packaged or deployedpackage– take the compiled code and package it in its distributable format, such as a JAR.verify– run any checks on results of integration tests to ensure quality criteria are metinstall– install the package into the local repository, for use as a dependency in other projects locallydeploy– done in the build environment, copies the final package to the remote repository for sharing with other developers and projects.

- Phases are made of plugin goals

- Execution requires the name of a phase or goal (dependent goals will get executed)

- Convention over configuration: sensible defaults

What if there is no plugin for something peculiar of the project?

A meta-build lifecycle: a lifecycle for build lifecycles

- Initialization: understand what is part of a build

- Configuration: create the necessary phases / goals and configure them

- Define the goals (or tasks)

- Configure the options

- Define dependencies among tasks

- Forming a directed acyclic graph

- Execution: run the tasks necessary to achieve the build goal

Rather than declaratively fit the build into a predefined lifecycle, declaratively define a build lifecycle

$\Rightarrow$ Typical of hybrid automators

Gradle

A paradigmatic example of a hybrid automator:

- Written mostly in Java

- with an outer Groovy layer and DSL

- …and, more recently, a Kotlin layer and DSL

Our approach to Gradle

- We are not going to learn “how to use Gradle”

- We are going to explore how to drive Gradle from scratch

- Gradle is flexible enough to allow an exploration of its core concepts

- It will work as an exemplary case for most hybrid automators

- Other automation systems can be driven similarly once the basics are understood

Gradle: main concepts

- Project – A collection of files composing the software

- The root project can contain subprojects

- Build file – A special file, with the build information

- situated in the root directory of a project

- instructs Gradle on the organization of the project

- Dependency – A resource required by some operation.

- May have dependencies itself

- Dependencies of dependencies are called transitive dependencies

- Configuration – A group of dependencies with three roles:

- Declare dependencies

- Resolve dependency declarations to actual artifacts/resources

- Present the dependencies to consumers in a suitable format

- Task – An atomic operation on the project, which can

- have input and output files

- depend on other tasks (can be executed only if those are completed)

- Tasks bridge the declarative and imperative worlds

Gradle from scratch: empty project

Let’s start as empty as possible, just point your terminal to an empty folder and:

touch build.gradle.kts

gradle tasks

Stuff happens: if nothing is specified,

Gradle considers the folder where it is invoked as a project

The project name matches the folder name

Let’s understand what:

Welcome to Gradle <version>!

Here are the highlights of this release:

- Blah blah blah

Starting a Gradle Daemon (subsequent builds will be faster)

Up to there, it’s just performance stuff: Gradle uses a background service to speed up cacheable operations

Gradle from scratch: empty project

> Task :tasks

------------------------------------------------------------

Tasks runnable from root project

------------------------------------------------------------

Build Setup tasks

-----------------

init - Initializes a new Gradle build.

wrapper - Generates Gradle wrapper files.

Some tasks exist already! They are built-in. Let’s ignore them for now.

Gradle from scratch: empty project

Help tasks

----------

buildEnvironment - Displays all buildscript dependencies declared in root project '00-empty'.

components - Displays the components produced by root project '00-empty'. [incubating]

dependencies - Displays all dependencies declared in root project '00-empty'.

dependencyInsight - Displays the insight into a specific dependency in root project '00-empty'.

dependentComponents - Displays the dependent components of components in root project '00-empty'. [incubating]

help - Displays a help message.

model - Displays the configuration model of root project '00-empty'. [incubating]

outgoingVariants - Displays the outgoing variants of root project '00-empty'.

projects - Displays the sub-projects of root project '00-empty'.

properties - Displays the properties of root project '00-empty'.

tasks - Displays the tasks runnable from root project '00-empty'.

Informational tasks. Among them, the tasks task we just invoked

Gradle: configuration vs execution

It is time to create our first task

Create a build.gradle.kts file as follows:

tasks.register("brokenTask") { // creates a new task

println("this is executed at CONFIGURATION time!")

}

Now launch gradle with gradle brokenTask:

gradle broken

this is executed at CONFIGURATION time!

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 378ms

Looks ok, but it’s utterly broken

Gradle: configuration vs execution

Try launching gradle tasks

- We do not expect our task to run, we are launching something else

❯ gradle tasks

> Task :tasks

------------------------------------------------------------

Tasks runnable from root project

------------------------------------------------------------

this is executed at CONFIGURATION time!

Build Setup tasks

Ouch!

Reason: the build script executes when Gradle is invoked, and configures tasks and dependencies.

Only later, when a task is invoked, the block gets actually executed

Gradle: configuration vs execution

Let’s write a correct task

tasks.register("helloWorld") {

doLast { // This method takes as argument a Task.() -> Unit

println("Hello, World!")

}

}

Execution with gradle helloWorld

gradle helloWorld

> Task :helloWorld

Hello, World!

Gradle: configuration vs execution

- The build configuration happens first

- Tasks and their dependencies are a result of the configuration

- The task execution happens later

- As per the “meta-lifecycle” discussed before

Delaying the execution allows for more flexible configuration

This will be especially useful when modifying existing behavior

val helloWorld = tasks.register("helloWorld") {

doLast { // This method takes as argument a Task.() -> Unit

println("Hello, World!")

}

}

helloWorld.configure { // Note the `configure` method: late configuration of the task

doFirst {

println("About to say hello...")

}

}

output of gradle helloWorld:

Configuring task: helloWorld

> Task :helloWorld

About to say hello...

Hello, World!

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 231ms

1 actionable task: 1 executed

Gradle: configuration avoidance

While task execution happens only for those tasks that are invoked (or their dependencies), task configuration happens for all tasks declared in the build script.

- This can lead to performance issues in large builds

In Gradle, tasks are registered lazily, and can be configured lazily as well, using the configure and configureEach methods.

val helloWorld = tasks.register("helloWorld") {

doLast { // This method takes as argument a Task.() -> Unit

println("Hello, World!")

}

}

helloWorld.configure { // Note the `configure` method: late configuration of the task

doFirst {

println("About to say hello...")

}

}

tasks.withType<Task>().configureEach {

println("Configuring task: ${this.name}")

doLast {

println("Finished task: ${this.name}")

}

doFirst {

println("Starting task: ${this.name}")

}

}

gradle helloWorld output:

Configuring task: helloWorld

> Task :helloWorld

Starting task: helloWorld

About to say hello...

Hello, World!

Finished task: helloWorld

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 395ms

1 actionable task: 1 executed

gradle tasks output:

Configuring task: tasks

> Task :tasks

Starting task: tasks

Configuring task: help # Configuration happens only when a task is needed!

Configuring task: projects

... list of tasks ...

Configuring task: helloWorld

------------------------------------------------------------

Tasks runnable from root project 'configuration-avoidance'

------------------------------------------------------------

... list of tasks ...

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 239ms

1 actionable task: 1 executed

Gradle: task types

Gradle offers some facilities to make writing new tasks easier

An example is the org.gradle.api.Exec task type, representing a command to be executed on the underlying command line

The task type can be specified at task registration time.

Any open class implementing org.gradle.api.Task can be instanced.

Tasks of unspecified type are plain DefaultTasks

import org.gradle.internal.jvm.Jvm // Jvm is part of the Gradle API

tasks.register<Exec>("printJavaVersion") { // Do you Recognize this? inline function with reified type!

// Configuration action is of type T.() -> Unit, in this case Exec.T() -> Unit

val javaExecutable = Jvm.current().javaExecutable.absolutePath

commandLine( // this is a method of class org.gradle.api.Exec

javaExecutable, "-version"

)

// There is no need of doLast / doFirst, actions are already configured

// Still, we may want to do something before or after the task has been executed

doLast { println("$javaExecutable invocation complete") }

doFirst { println("Ready to invoke $javaExecutable") }

}

> Task :printJavaVersion

Ready to invoke /usr/lib/jvm/java-11-openjdk/bin/java

openjdk version "11.0.8" 2020-07-14

OpenJDK Runtime Environment (build 11.0.8+10)

OpenJDK 64-Bit Server VM (build 11.0.8+10, mixed mode)

/usr/lib/jvm/java-11-openjdk/bin/java invocation complete

Gradle: compiling from scratch

Let’s compile a simple src/HelloWorld.java:

class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String... args) {

System.out.println("Hello, World!");

}

}

Build logic:

- Find the Java compiler executable

- Find the sources to be compiled

- Invoke

javac -d destination <files>

Which step should be in configuration, and which in execution?

General rule: move as much as possible to execution

- The less is done at configuration time, the faster the build when the task is not executed

- Delaying to execution allows for more flexible configuration

Lazy configuration, inputs, outputs

tasks.register<Exec>("compileJava") {

// Computed at configuration time

val sources = TODO("assume this is expensive")

// configuration that needs "sources"

doFirst { // We need to compute the sources and classpath as late as possible!

sources.forEach { ... }

}

}

- Problem: we need to run the expensive operation even if the task is not executed!

- We must delay the execution as much as possible

- Problem: other tasks may generate sources, and should thus run before

- We must understand that the output of some tasks is the input of other tasks

Task inputs and outputs

How can Gradle determine which tasks some task depends on?

- Explicit dependencies (later)

- Implicit dependencies, via inputs and outputs

- If a task input is the output of another task, then the first task depends on the second

Inputs and outputs can be configured via the inputs and outputs properties of a task.

Inputs and outputs are also used by Gradle to determine if a task is UP-TO-DATE,

namely, if it can be skipped because its inputs have not changed since the last execution.

- This is called incremental build.

- Large builds can be sped up significantly.

Lazy configuration in Gradle

Gradle supports the construction of lazy properties and providers:

- Wire together Gradle components without worrying about values, just knowing their provider.

- Configuration happens before execution, some values are unknown

- yet their provider is known at configuration time

In the gradle API

Provider – a value that can only be queried and cannot be changed

- Transformable through a

mapmethod - Easily built via

project.provider { ... }(projectcan be omitted in build scripts)

Property – a value that can be queried and also changed

- Subtype of Provider

- Can be

setby passing a value or aProvider - A new property can be created via

project.objects.property<Type>()(projectcan be omitted in build scripts)

import org.gradle.internal.jvm.Jvm

tasks.register<Exec>("compileJava") { // This is a Kotlin lambda with receiver!

val sourceDir = projectDir.resolve("src")

inputs.dir(sourceDir)

val outputDir = layout.buildDirectory.dir("bin").get().asFile.absolutePath

outputs.dir(outputDir)

val javacExecutable = Jvm.current().javacExecutable.absolutePath // Use the current JVM's javac

executable(javacExecutable)

doFirst { // We need to compute the sources and classpath as late as possible

val sources = sourceDir.walkTopDown().filter { it.isFile && it.extension == "java" }.toList()

println(sources)

when {

sources.isEmpty() -> {

println("No source files found, skipping compilation.")

args("-version")

}

else -> args(

// destination folder: the output directory of Gradle, inside "bin"

"-d", outputDir,

*sources.toTypedArray(),

)

}

}

}

Execution:

gradle compileJava

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 693ms

Compiled files are in build/bin!

Gradle: dependency management

Dependency management in Gradle is rooted in two fundamental concepts:

- Dependency, a resource of some kind, possibly having other (transitive) dependencies

- Configuration, a resolvable (mappable to actual resources) set of dependencies

- $\Rightarrow$ Not to be confused with the configuration phase!

Let’s see a use case: compiling a Java source with a dependency

- In

javacterms, we need to feed some jars to the-cpflag of the compiler - In Gradle (automation) terms, we need:

- a configuration representing the compile classpath

- one dependency for each library we need to compile

Gradle: dependency management

Conceptually, we want something like:

// Gradle way to create a configuration

val compileClasspath ... // Delegation!

dependencies {

compileClasspath.add(dir("libs").files.filter { it.extension == "jar" })

}

To be consumed by our improved compile task:

tasks.register<Exec>("compileJava") {

...

else -> args(

"-d", outputDir,

// classpath from the configuration

"-cp", "${File.pathSeparator}${compileClasspath.asPath}",

*sources.toTypedArray(),

)

}

Gradle: using custom configurations

A minimal DSL to simplify file access:

// Minimal file access DSL

object AllFiles

val Project.allFiles: AllFiles get() = AllFiles // We need this to prevent "Object AllFiles captures the script class instance" error

data class Finder(val path: File) {

fun withExtension(extension: String): List<File> =

path.walkTopDown().filter { it.isFile && it.extension == extension }.toList()

}

fun AllFiles.inFolder(path: String) = Finder(projectDir.resolve(path))

Dependency declaration (configuration time):

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating // Delegation!

dependencies { // built-in in Gradle

AllFiles.inFolder("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach { // Not Gradle: defined below

compileClasspath(files(it)) // The Configuration class overrides the invoke operator

}

}

Dependency use (execution time):

doFirst { // We need to compute the sources and classpath as late as possible

val sources = AllFiles.inFolder("src").withExtension("java")

println(sources)

when {

sources.isEmpty() -> {

println("No source files found, skipping compilation.")

args("-version")

}

else -> args(

// destination folder: the output directory of Gradle, inside "bin"

"-d", outputDir,

// classpath from the configuration

"-cp", "${File.pathSeparator}${compileClasspath.asPath}",

*sources.toTypedArray(),

)

}

}

Gradle: using custom configurations

Full example:

import org.gradle.internal.jvm.Jvm

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating // Delegation!

dependencies { // built-in in Gradle

AllFiles.inFolder("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach { // Not Gradle: defined below

compileClasspath(files(it)) // The Configuration class overrides the invoke operator

}

}

tasks.register<Exec>("compileJava") { // This is a Kotlin lambda with receiver!

inputs.dir(projectDir.resolve("src"))

val outputDir = layout.buildDirectory.dir("bin").get().asFile.absolutePath

outputs.dir(outputDir)

val javacExecutable = Jvm.current().javacExecutable.absolutePath // Use the current JVM's javac

executable(javacExecutable)

doFirst { // We need to compute the sources and classpath as late as possible

val sources = AllFiles.inFolder("src").withExtension("java")

println(sources)

when {

sources.isEmpty() -> {

println("No source files found, skipping compilation.")

args("-version")

}

else -> args(

// destination folder: the output directory of Gradle, inside "bin"

"-d", outputDir,

// classpath from the configuration

"-cp", "${File.pathSeparator}${compileClasspath.asPath}",

*sources.toTypedArray(),

)

}

}

}

// Minimal file access DSL

object AllFiles

val Project.allFiles: AllFiles get() = AllFiles // We need this to prevent "Object AllFiles captures the script class instance" error

data class Finder(val path: File) {

fun withExtension(extension: String): List<File> =

path.walkTopDown().filter { it.isFile && it.extension == extension }.toList()

}

fun AllFiles.inFolder(path: String) = Finder(projectDir.resolve(path))

Gradle: task dependencies

Next step: we can compile, why not executing the program as well?

- Let’s define a

runtimeClasspathconfiguration- “inherits” from

compileClasspath - includes the output folder

- In general we may need stuff at runtime that we don’t need at compile time

- E.g. stuff loaded via reflection

- “inherits” from

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating

val runtimeClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating {

extendsFrom(compileClasspath)

}

dependencies { // built-in in Gradle

AllFiles.inFolder("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach { // Not Gradle: defined below

compileClasspath(files(it)) // The Configuration class overrides the invoke operator

}

}

- Let’s write the task

tasks.register<Exec>("runJava") {

inputs.dir(compilationDestination)

dependsOn(compileJava) // IMPORTANT! This is a task dependency, we must compile before running

executable(Jvm.current().javaExecutable.absolutePath)

doFirst {

args(

"-cp", "${compilationDestination}${File.pathSeparator}${runtimeClasspath.asPath}",

"HelloMath",

)

}

}

import org.gradle.internal.jvm.Jvm

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating

val runtimeClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating {

extendsFrom(compileClasspath)

}

dependencies { // built-in in Gradle

AllFiles.inFolder("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach { // Not Gradle: defined below

compileClasspath(files(it)) // The Configuration class overrides the invoke operator

}

}

val compilationDestination: String = layout.buildDirectory.dir("bin").get().asFile.absolutePath

val compileJava = tasks.register<Exec>("compileJava") { // This is a Kotlin lambda with receiver!

inputs.dir(projectDir.resolve("src"))

outputs.dir(compilationDestination)

val javacExecutable = Jvm.current().javacExecutable.absolutePath // Use the current JVM's javac

executable(javacExecutable)

doFirst { // We need to compute the sources and classpath as late as possible

val sources = AllFiles.inFolder("src").withExtension("java")

println(sources)

when {

sources.isEmpty() -> {

println("No source files found, skipping compilation.")

args("-version")

}

else -> args(

// destination folder: the output directory of Gradle, inside "bin"

"-d", compilationDestination,

// classpath from the configuration

"-cp", "${File.pathSeparator}${compileClasspath.asPath}",

*sources.toTypedArray(),

)

}

}

}

tasks.register<Exec>("runJava") {

inputs.dir(compilationDestination)

dependsOn(compileJava) // IMPORTANT! This is a task dependency, we must compile before running

executable(Jvm.current().javaExecutable.absolutePath)

doFirst {

args(

"-cp", "${compilationDestination}${File.pathSeparator}${runtimeClasspath.asPath}",

"HelloMath",

)

}

}

// Minimal file access DSL

object AllFiles

val Project.allFiles: AllFiles get() = AllFiles // We need this to prevent "Object AllFiles captures the script class instance" error

data class Finder(val path: File) {

fun withExtension(extension: String): List<File> =

path.walkTopDown().filter { it.isFile && it.extension == extension }.toList()

}

fun AllFiles.inFolder(path: String) = Finder(projectDir.resolve(path))

Gradle: task dependencies

Let us temporarily comment:

dependsOn(compileJava) // IMPORTANT! This is a task dependency, we must compile before running

and run:

> Task :runJava FAILED

[Incubating] Problems report is available at: file:///home/danysk/LocalProjects/spe-slides/examples/run-java-deps/build/reports/problems/problems-report.html

FAILURE: Build failed with an exception.

* What went wrong:

A problem was found with the configuration of task ':runJava' (type 'Exec').

- Type 'org.gradle.api.tasks.Exec' property '$1' specifies directory '/home/danysk/LocalProjects/spe-slides/examples/run-java-deps/build/bin' which doesn't exist.

Reason: An input file was expected to be present but it doesn't exist.

Possible solutions:

1. Make sure the directory exists before the task is called.

2. Make sure that the task which produces the directory is declared as an input. # <<<< OUR PROBLEM!!

For more information, please refer to https://docs.gradle.org/8.14/userguide/validation_problems.html#input_file_does_not_exist in the Gradle documentation.

* Try:

> Make sure the directory exists before the task is called

> Make sure that the task which produces the directory is declared as an input

> Run with --scan to get full insights.

BUILD FAILED in 752ms

1 actionable task: 1 executed

$\Rightarrow$ The code was not compiled!

- We need

runJavato run aftercompileJava - One task depends on another!

Gradle: task dependencies

gradle runJava with the dependency correctly set:

> Task :compileJava

[/home/danysk/LocalProjects/spe-slides/examples/run-java-deps/src/HelloMath.java]

> Task :runJava

avg=3.0, std.dev=1.5811388300841898

regression: y = 2.0300000000000002 * x + -0.030000000000001137

R²=0.998957626296907

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 581ms

2 actionable tasks: 2 executed

Build automation: dependencies everywhere

Dependencies permeate the world of build automation.

- At the “task” level

- Compile dependencies

- Runtime dependencies

- At the “build” level

- Phases of the lifecycle (configurations in Gradle) depend on other phases

- Tasks depend on other tasks

$\Rightarrow$ at the global level as well!

no guarantee that automation written with some tool at version X, will work at version Y!

The Gradle wrapper

- A global dependency on the build tool is hard to capture

- Often, it becomes a prerequisite expressed in natural language

- e.g., “you need Maven 3.6.1 to build this software”

- Critical issues when different pieces of the same system depend on different build tool versions

Gradle proposes a (partial) solution with the so-called Gradle wrapper

- A minimal program that simply downloads the version of gradle written in a configuration file

- Generable with the built-in task

wrappergradle wrapper --gradle-version=<VERSION>

- Prepares scripts for bash and cmd to run Gradle at the specified version

gradlewgradlew.bat

The Gradle wrapper is the correct way to use gradle, and we’ll be using it from now on.

Mixed imperativity and declarativity

At the moment, we have part of the project that’s declarative, and part that’s imperative:

- Declarative

- configurations and their relationships

- dependencies

- task dependencies

- Imperative

- Operations on the file system

- some of the actual task logics

- resolution of configurations

The declarative part is the one for which we had a built-in API for!

Unavoidability of imperativity

(and its isolation)

The base mechanism at work here is hiding imperativity under a clean, declarative API.

Also “purely declarative” build systems, such as Maven, which are driven with markup files, hide their imperativity behind a curtain (in the case of Maven, plugins that are configured in the pom.xml, but implemented elsewhere).

Usability, understandability, and, ultimately, maintability, get increased when:

- Imperativity gets hidden under the hood

- Most (if not all) the operations can be configured rather than written

- Configuration can be minimal for common tasks

- Convention over configuration, we’ll get back to this

- Users can resort to imperativity in case of need

Isolation of imperativity

Task type definition

Let’s begin our operation of isolation of imperativity by refactoring our hierarchy of operations.

- We have a number of “Java-related” tasks.

- All of them have a classpath

- All of them have an executable that depend on the operation they perform

- One has an output directory and input sources

- One has a “main class” input

interface TaskWithClasspath : Task {

val classpath: Property<FileCollection>

}

interface JavaCompileTask : TaskWithClasspath {

val sources: Property<FileCollection>

val destinationDir: DirectoryProperty

}

interface JavaRunTask : TaskWithClasspath {

val mainClass: Property<String>

}

Isolation of imperativity

Task design

Next step: let’s inherit the behavior of our tasks from Exec:

Creating a new Task type in Gradle

Gradle supports the definition of new task types:

- New tasks must implement the

Taskinterface- They usually inherit from

DefaultTask

- They usually inherit from

- They must be

abstract- Gradle creates subclasses on the fly under the hood and injects methods

- A public method can be marked as

@TaskAction, and will get invoked to execute the task

Input, output, caching, and continuous build mode

In recent Gradle versions, it is mandatory to annotate every public property’s getter of a task with a marker annotation for gradle to mark it as an input or an output.

@Input,@InputFile,@InputFiles,@InputDirectory,@InputDirectories,@Classpath@OutputFile,@OutputFiles,@OutputDirectory,@OutputDirectories@Internalmarks internal output properties (not reified on the file system)@Internalmarks internal output properties (not reified on the file system)

- In practice, these appear in Kotlin code as

@get:Input, etc.- Otherwise, Kotlin would generate the annotation on the field, not on the getter, and Gradle would ignore it

Why?

- Performance

- Gradle caches intermediate build results, using input and output markers to undersand whether or not some task is up to date

- This allows for much faster builds while working on large projects

- Time to build completion can decrease a dozen minutes to seconds!

- Continuous build

- Re-run tasks upon changes with the

-toption - (In/Out)put markers are used to understand what to re-run

- Re-run tasks upon changes with the

Custom Task types in Gradle

abstract class AbstractJvmExec : TaskWithClasspath, Exec() {

@get:Classpath

override val classpath: Property<FileCollection> = project.objects.property()

init {

executable(Jvm.current().jvmExecutableForTask().absolutePath)

}

// Extension function with virtual dispatch receiver!

protected abstract fun Jvm.jvmExecutableForTask(): File

}

abstract class JavaRun() : JavaRunTask, AbstractJvmExec() {

@get:Input

override val mainClass: Property<String> = project.objects.property()

override fun Jvm.jvmExecutableForTask(): File = javaExecutable

@TaskAction

override fun exec() {

args(

"-cp", classpath.get().asPath,

mainClass.get(),

)

super.exec()

}

}

abstract class JavaCompile: JavaCompileTask, AbstractJvmExec() {

@get:InputFiles

override val sources: Property<FileCollection> = project.objects.property()

@get:OutputDirectory

override val destinationDir: DirectoryProperty = project.objects.directoryProperty()

override fun Jvm.jvmExecutableForTask(): File = javacExecutable

@TaskAction

override fun exec() {

when {

sources.get().isEmpty -> {

println("No source files found, skipping compilation.")

args("-version")

}

else -> args(

// destination folder: the output directory of Gradle, inside "bin"

"-d", destinationDir.get().asFile.absolutePath,

// classpath from the configuration

"-cp", "${File.pathSeparator}${classpath.get().asPath}",

*sources.get().files.toTypedArray(),

)

}

super.exec()

}

}

Isolation of imperativity

Problem

In our main build.gradle.kts, we have:

a declarative part

// DECLARATIVE (what)

val compilationDestination = layout.buildDirectory.dir("bin").get().asFile

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating

val runtimeClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating {

extendsFrom(compileClasspath)

}

dependencies { // built-in in Gradle

allFiles.inFolder("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach { // Not Gradle: defined below

compileClasspath(files(it)) // The Configuration class overrides the invoke operator

}

runtimeClasspath(files(compilationDestination))

}

tasks.register<JavaCompile>("compileJava") {

classpath = compileClasspath

destinationDir = compilationDestination

sources = files(project.allFiles.inFolder("src").withExtension("java"))

}

tasks.register<JavaRun>("runJava") {

classpath = runtimeClasspath

mainClass = "HelloMath"

dependsOn(tasks.named("compileJava"))

}

an imperative part

// IMPERATIVE (how)

// Minimal file access DSL

object AllFiles

val Project.allFiles: AllFiles get() = AllFiles // We need this to prevent "Object AllFiles captures the script class instance" error

data class Finder(val path: File) {

fun withExtension(extension: String): List<File> =

path.walkTopDown().filter { it.isFile && it.extension == extension }.toList()

}

fun AllFiles.inFolder(path: String) = Finder(projectDir.resolve(path))

interface TaskWithClasspath : Task {

val classpath: Property<FileCollection>

}

interface JavaCompileTask : TaskWithClasspath {

val sources: Property<FileCollection>

val destinationDir: DirectoryProperty

}

interface JavaRunTask : TaskWithClasspath {

val mainClass: Property<String>

}

abstract class AbstractJvmExec : TaskWithClasspath, Exec() {

(continues a lot further)

Idea

Hide the imperative part under the hood, and expose a purely declarative API to the user.

Isolation of imperativity

Project-wise API extension

Gradle provides a way to define project-wise build APIs using a special buildSrc folder

- Requires a Gradle configuration file

- What it actually does will be clearer in future

Directory structure:

project-folder

├── build.gradle.kts

├── buildSrc

│ ├── build.gradle.kts

│ └── src

│ └── main

│ └── kotlin

│ ├── ImperativeAPI.kt

│ └── MoreImperativeAPIs.kt

└── settings.gradle.kts

buildSrc/build.gradle.kts’ contents (clearer in future):

plugins {

`kotlin-dsl`

}

repositories {

mavenCentral()

}

Isolation of imperativity

Project-wise API extension

Directory structure for our Java infrastructure:

examples/buildsrc

├── build.gradle.kts

├── buildSrc

│ ├── build.gradle.kts

│ └── src

│ └── main

│ └── kotlin

│ ├── AllFiles.kt

│ ├── JavaCompile.kt

│ ├── JavaRun.kt

│ └── JavaTasksAPI.kt

├── gradlew

├── gradlew.bat

├── libs

│ └── commons-math3-3.6.1.jar

└── src

└── HelloMath.java

our new build.gradle.kts:

val compilationDestination = project.layout.buildDirectory.dir("bin").get().asFile

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating

val runtimeClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating {

extendsFrom(compileClasspath)

}

dependencies {

allFilesIn("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach {

compileClasspath(files(it))

}

runtimeClasspath(files(compilationDestination))

}

tasks.register<JavaCompile>("compileJava") {

classpath = compileClasspath

destinationDir = compilationDestination

sources = files(allFilesIn("src").withExtension("java"))

}

tasks.register<JavaRun>("runJava") {

classpath = runtimeClasspath

dependsOn(tasks.named("compileJava"))

}

we can use all types defined in buildSrc/src/main/kotlin/ in the main project’s build.gradle.kts!

Isolation of imperativity

Project-wise conventions

What our build.gradle.kts defines is now a convention for Java projects:

val compilationDestination = project.layout.buildDirectory.dir("bin").get().asFile

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating

val runtimeClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating {

extendsFrom(compileClasspath)

}

dependencies {

allFilesIn("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach {

compileClasspath(files(it))

}

runtimeClasspath(files(compilationDestination))

}

tasks.register<JavaCompile>("compileJava") {

classpath = compileClasspath

destinationDir = compilationDestination

sources = files(allFilesIn("src").withExtension("java"))

}

tasks.register<JavaRun>("runJava") {

classpath = runtimeClasspath

dependsOn(tasks.named("compileJava"))

}

- There exist two configurations:

compileClasspathruntimeClasspath, which extends fromcompileClasspath

- All jars in

libsare added to both configurations - There is a

compileJavatask that compiles all Java sources insrc - There is a

runJavatask that runs a specified main class

These could be valid for any Java project!

Isolation of imperativity

Project-wise conventions

- Conventional build logic can be defined in

buildSrc/src/main/kotlin/convention-name.gradle.kts, - and imported in the main

build.gradle.ktsvia:

plugins {

id("convention-name")

}

buildSrc/src/main/kotlin/java-convention.gradle.kts:

val compilationDestination = project.layout.buildDirectory.dir("bin").get().asFile

val compileClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating

val runtimeClasspath: Configuration by configurations.creating {

extendsFrom(compileClasspath)

}

dependencies {

allFilesIn("libs").withExtension("jar").forEach {

compileClasspath(files(it))

}

runtimeClasspath(files(compilationDestination))

}

tasks.register<JavaCompile>("compileJava") {

classpath = compileClasspath

destinationDir = compilationDestination

sources = files(allFilesIn("src").withExtension("java"))

}

tasks.register<JavaRun>("runJava") {

classpath = runtimeClasspath

dependsOn(tasks.named("compileJava"))

}

build.gradle.kts:

plugins {

id("java-convention")

}

tasks.runJava.configure { // We must set the main class here

mainClass = "HelloMath"

}

Build hierarchies

Sometimes projects are modular

Where a module is a sub-project with a clear identity, possibly reusable elsewhere

Examples:

- A smartphone application with:

- A common library

- A software that uses such library for the actual app

- Bluetooth control software comprising:

- Platform-specific drivers

- A platform-agnostic bluetooth API and service

- A CLI interface to the library

- A Graphical interface

Modular software simplifies maintenance and improves understandability

Modules may depend on other modules

Some build tasks of some module may require build tasks of other modules to be complete before execution

Hierarchial project

Let us split our project into two components:

- A base library

- A stand-alone application using the library

We need to reorganize the build logic to something similar to

hierarchial-project

|__:library

\__:app

Desiderata:

- We can compile any of the two projects from the root

- We can run the app from the root

- Calling a run of the app implies a compilation of the library

- We can clean both projects

Authoring subprojects in Gradle

Gradle (as many other build automators)

offers built-in support for hierarchial projects.

Gradle is limited to two levels, other products such as Maven have no limitation

Subprojects are listed in a settings.gradle.kts file

Incidentally, it’s the same place where the project name can be specified

Subprojects must have their own build.gradle.kts

They can also have their own settings.gradle.kts, e.g. for selecting a name different than their folder

Authoring subprojects in Gradle

- Create a settings.gradle.kts and declare your modules:

rootProject.name = "project-with-hierarchy"

include(":library") // There must be a folder named "library"

include(":app") // There must be a folder named "app"

- In the root project, configure the part common to all projects (included the root project) in a

allprojectsblock

allprojects {

// Executed for every project, included the root one

// here, `project` refers to the current project

}

- Put the part shared by solely the sub-projects into a

subprojectsblock

subprojects {

// Executed for all subprojects

// here, `project` refers to the current project

}

- In each subproject’s

build.gradle.kts, add further customization as necessary - Connect configurations to each other using dependencies

dependencies {

compileClasspath(project(":library")) { // My compileClasspath configuration depends on project library

targetConfiguration = "runtimeClasspath" // Specifically, from its runtime

}

}

- Declare inter-subproject task dependencies

- Tasks may fail if ran out of order! Compiling

apprequireslibraryto be compiled.

- Tasks may fail if ran out of order! Compiling

tasks.compileJava { dependsOn(project(":library").tasks.compileJava) }

Reusability across multiple projects

We now have a rudimental infrastructure for building and running Java projects

What if we want to reuse it?

Of course, copy/pasting the same file across projects is to be avoided whenever possible

The concept of plugin

Gradle (as many other build systems) allow extensibility via plugins

A plugin is a software component that extends the API of the base system

It usually includes:

- A set of

Tasks - An

Extension– An object incapsulating the global configuration options- leveraging an appropriate DSL

- A

Pluginobject, implementing anapply(Project)function- Application must create the extension, the tasks, and the rest of the imperative stuff

- A manifest file declaring which of the classes implementing

Pluginis the entry point of the declared plugin- located in

META-INF/gradle-plugins/<plugin-name>.properties

- located in

Divide, conquer, encapsulate, adorn

General approach to a new build automation problem:

Divide: Identify the base steps, they could become your tasks

- Or any concept your build system exposes to model atomic operations

Conquer: Clearly express the dependencies among them

- Build a pipeline

- Implement them Providing a clean API

Encapsulate: confine imperative logic, make it an implementation detail

Adorn: provide a DSL that makes the library easy and intuitive

Not very different than what’s usually done in (good) software development

Using a plugin

- Plugins are loaded from the build environment

- the classpath used for such tasks can be explored with the built-in task

buildEnvironment - if a plugin is not found, then if a version for it is available it’s fetched from remote repositories

- by default the Gradle plugin portal

- the classpath used for such tasks can be explored with the built-in task

- Plugins need to be applied

- Which actually translates to calling the

apply(Project)function - Application for hierarchial projects is not automatic

- You might want your plugin to be applied only in some subprojects!

- Which actually translates to calling the

Example code

plugins {

pluginName // Loads a plugin from the "buildEnvironment" classpath

`plugin-name` // Syntax for non Kotlin-compliant plugin names

id("plugin2-name") // Alternative to the former

id("some-custom-plugin") version "1.2.3" // if not found locally, gets fetched from the Gradle plugin portal

}

// In case of non-hierarchial projects, plugins are also "applied"

// Otherwise, they need to get applied manually, e.g.:

allprojects {

apply(plugin = "pluginName")

}

Built-in Gradle plugins

The default Gradle distribution includes a large number of plugins, e.g.:

javaplugin, for Java written applications- a full fledged version of the custom local plugin we created!

java-libraryplugin, for Java libraries (with no main class)scalaplugincppplugin, for C++kotlinplugin, supporting Kotlin with multiple targets (JVM, Javascript, native)

We are going to use the Kotlin JVM plugin to build our first standalone plugin!

(yes we already did write our first one: code in buildSrc is project-local plugin code)

A Greeting plugin

A very simple plugin that greets the user

Desiderata

- adds a

greettask that prints a greeting - the default output should be configurable with something like:

plugins {

id("org.danilopianini.template-for-gradle-plugins")

}

hello {

author.set("Danilo Pianini")

}

Setting up a Kotlin build

First step: we need to set up a Kotlin build, we’ll write our plugin in Kotlin

plugins {

// No magic: calls a method running behind the scenes, equivalent to id("org.jetbrains.kotlin-$jvm")

kotlin("jvm") version "2.2.20" // version is necessary

}

The Kotlin plugin introduces tasks and configurations to compile and package Kotlin code

Second step: we need to declare where to find dependencies

- Maven repositories are a de-facto standard for shipping JVM libraries

// Configuration of software sources

repositories {

mavenCentral() // points to Maven Central

}

dependencies {

// "implementation" is a configuration created by by the Kotlin JVM plugin

implementation(...) // we can load libraries here

}

Third step, we need the Gradle API

dependencies {

implementation(gradleApi()) // Built-in method, returns a `Dependency` to the current Gradle version

api(gradleKotlinDsl()) // Built-in method, returns a `Dependency` to the Gradle Kotlin DSL library

}

Plugin name and entry point

Gradle expects the plugin entry point (the class implementing the Plugin interface) to be specified in a manifest file

- in a property file

- located in

META-INF/gradle-plugins - whose file name is

<plugin-name>.properties

The name is usually a “reverse url”, similarly to Java packages.

e.g., it.unibo.spe.greetings

The file content is just a pointer to the class implementing Plugin, for instance:

implementation-class=it.unibo.spe.firstplugin.GreetingPlugin

Plugin implementation

Usually, composed of:

- A clean API, if the controlled system is not trivial

- A set of tasks incapuslating the imperative logic

- An extension containing the DSL for configuring the plugin

- A plugin

- Creates the extension

- Creates the tasks

- Links tasks and extension

A Gradle plugin implementation

inside src/main/kotlin/<package-path>/:

HelloTask implementation:

open class HelloTask : DefaultTask() {

/**

* The author of the greeting, lazily set.

*/

@get:Input

val author: Property<String> = project.objects.property()

/**

* Read-only property calculated from the greeting.

*/

@get:Internal

val message: Provider<String> = author.map { "Hello from $it" }

/**

* This is the code that is executed when the task is run.

*/

@TaskAction

fun printMessage() {

logger.quiet(message.get())

}

}

HelloExtension, the DSL entrypoint:

open class HelloExtension(objects: ObjectFactory) {

/**

* This is where you write your DSL to control the plugin.

*/

val author: Property<String> = objects.property()

}

HelloGradle, the plugin entrypoint:

- whose

applymethod is called upon application

open class HelloGradle : Plugin<Project> {

override fun apply(target: Project) {

val extension = target.extensions.create<HelloExtension>("hello")

// Enables `hello { ... }` in build.gradle.kts

target.tasks.register<HelloTask>("hello") {

author.set(extension.author)

}

}

}

Plugin application from plugins and reaction to plugin applications

- The

Pluginconfigures the project as needed for the tasks and the extension to work - Plugins can forcibly apply other plugins

- e.g., the Kotlin plugin applies the

java-libraryplugin behind the scenes - although it is generally preferred to react to the application of other plugins

- e.g., the Kotlin plugin applies the

- Plugins can react to the application of other plugins

- e.g., enable additional features or provide compatibility

- doing so is possible by the

pluginsproperty ofProject, e.g.:

project.plugins.withType(JavaPlugin::class.java) {

// Stuff you want to do only if someone enables the Java plugin for the current project

}

Testing a plugin

- Push the gradle plugin into the build classpath

- Prepare a Gradle workspace

- Launch the tasks of interest

- Verify the task success (or failure, if expected), or the program output

Gradle provides a test kit, to launch Gradle programmatically and inspect the execution results

Importing the Gradle dependencies and the test kit

It’s just matter of pulling the right dependencies

dependencies {

implementation(gradleApi())

implementation(gradleKotlinDsl())

testImplementation(gradleTestKit()) // Test implementation: available for testing compile and testing runtime

}

Plugin Classpath injection

By default, the Gradle test kit just runs Gradle. We want to inject our plugin into the distribution:

- Create the list of files composing our runtime classpath

- Make sure that the list is always up to date and ready before test execution

- Use such list as our classpath for running Gradle

This operation is now built-in the test kit:

// Configure a Gradle runner

val runner = GradleRunner.create()

.withProjectDir()

.withPluginClasspath(classpath) // we need Gradle **and** our plugin

.withArguments(":tasks", ":you", ":need", ":to", ":run:", "--and", "--cli", "--options")

.build() // This actually runs Gradle

// Inspect results

runner.task(":someExistingTask")?.outcome shouldBe TaskOutcome.SUCCESS

runner.output shouldContain "Hello from Gradle"

DRY with dependencies declaration

Look at the following example code:

dependencies {

testImplementation("io.kotest:kotest-runner-junit5:4.2.5")

testImplementation("io.kotest:kotest-assertions-core:4.2.5")

testImplementation("io.kotest:kotest-assertions-core-jvm:4.2.5")

}

It is repetitive and fragile (what if you change the version of a single kotest module?)

Let’s patch all this fragility:

dependencies {

val kotestVersion = "4.2.5"

testImplementation("io.kotest:kotest-runner-junit5:$kotestVersion")

testImplementation("io.kotest:kotest-assertions-core:$kotestVersion")

testImplementation("io.kotest:kotest-assertions-core-jvm:$kotestVersion")

}

Still, quite repetitive…

DRY with dependencies declaration

dependencies {

val kotestVersion = "4.2.5"

fun kotest(module: String) = "io.kotest:kotest-$module:$kotestVersion"

testImplementation(kotest("runner-junit5")

testImplementation(kotest("assertions-core")

testImplementation(kotest("assertions-core-jvm")

}

Uhmm…

- it’s still repetitive (can be furter factorized by bundling the kotest modules)

- the function and version could be included in

buildSrc - custom solutions can be nice, but:

- they can be hard to understand, as they are not standard

- may make further automation harder (e.g., bots that run automatic updates may not be aware of your custom solution)

Declaring dependencies in a catalog

Gradle 7 introduced the catalogs, a standardized way to collect and bundle dependencies.

Catalogs can be declared in:

- the

build.gradle.ktsfile (they are API, of course) - a TOML configuration file (default:

gradle/libs.versions.toml)

[versions]

dokka = "2.0.0"

konf = "1.1.2"

kotest = "6.0.4"

kotlin = "2.2.21"

[libraries]

apache-commons-lang3 = "org.apache.commons:commons-lang3:3.20.0"

classgraph = "io.github.classgraph:classgraph:4.8.184"

konf-yaml = { module = "com.uchuhimo:konf-yaml", version.ref = "konf" }

kotest-junit5-jvm = { module = "io.kotest:kotest-runner-junit5-jvm", version.ref = "kotest" }

kotest-assertions-core-jvm = { module = "io.kotest:kotest-assertions-core-jvm", version.ref = "kotest" }

[bundles]

kotlin-testing = [ "kotest-junit5-jvm", "kotest-assertions-core-jvm" ]

[plugins]

dokka = { id = "org.jetbrains.dokka", version.ref = "dokka" }

gitSemVer = "org.danilopianini.git-sensitive-semantic-versioning:7.0.6"

gradlePluginPublish = "com.gradle.plugin-publish:2.0.0"

jacoco-testkit = "pl.droidsonroids.jacoco.testkit:1.0.12"

kotlin-jvm = { id = "org.jetbrains.kotlin.jvm", version.ref = "kotlin" }

kotlin-qa = "org.danilopianini.gradle-kotlin-qa:0.98.0"

multiJvmTesting = "org.danilopianini.multi-jvm-test-plugin:4.3.2"

publishOnCentral = "org.danilopianini.publish-on-central:9.1.7"

taskTree = "com.dorongold.task-tree:4.0.1"

Gradle generates type-safe accessors for the definitions:

dependencies {

api(gradleApi())

api(gradleKotlinDsl())

api(kotlin("stdlib-jdk8"))

testImplementation(gradleTestKit())

testImplementation(libs.apache.commons.lang3)

testImplementation(libs.konf.yaml)

testImplementation(libs.classgraph)

testImplementation(libs.bundles.kotlin.testing)

}

Also for the plugins:

plugins {

`java-gradle-plugin`

alias(libs.plugins.dokka)

alias(libs.plugins.gitSemVer)

alias(libs.plugins.gradlePluginPublish)

alias(libs.plugins.jacoco.testkit)

alias(libs.plugins.kotlin.jvm)

alias(libs.plugins.kotlin.qa)

alias(libs.plugins.publishOnCentral)

alias(libs.plugins.multiJvmTesting)

alias(libs.plugins.taskTree)

}

Build vs. Compile vs. Test toolchains

We now have three different runtimes at play:

- One or more compilation targets

- In case of JVM projects, the target bytecode version

- In case of .NET projects, the target .NET

- In case of native projects, the target OS / architecture

- One or more runtime targets

- In case of JVM or .NET projects the virtual machines we want to support

- A built-time runtime

- In case of Gradle, the JVM running the build system

These toolchains should be controlled indipendently!

You may want to use Java 17 to run Gradle, but compile in a Java 8-compatible bytecode, and then test on Java 11.

Gradle and the toolchains

Default behaviour: Gradle uses the same JVM it is running in as:

- build runtime (you don’t say)

- compile target

- test runtime

Supporting multiple toolchains may not be easy!

- Cross-compilers?

- Automatic retrieval of runtime environments?

- Emulators for native devices?

Targeting a portable runtime (such as the JVM) helps a lot.

Introducing the Gradle toolchains

Define the reference toolchain version (compilation target):

java {

toolchain {

languageVersion.set(JavaLanguageVersion.of(11))

vendor.set(JvmVendorSpec.ADOPTOPENJDK) // Optionally, specify a vendor

implementation.set(JvmImplementation.J9) // Optionally, select an implementation

}

}

Create tasks for running tests on specific environments:

tasks.withType<Test>().toList().takeIf { it.size == 1 }?.let{ it.first }.run {

// If there exist a "test" task, run it with some specific JVM version

javaLauncher.set(javaToolchains.launcherFor { languageVersion.set(JavaLanguageVersion.of(8)) })

}

// Register another test task, with a different JVM

val testWithJVM17 by tasks.registering<Test> { // Also works with JavaExec

javaLauncher.set(javaToolchains.launcherFor { languageVersion.set(JavaLanguageVersion.of(17)) })

} // You can pick JVM's not yet supported by Gradle!

tasks.findByName("check")?.configure { it.dependsOn(testWithJVM17) } // make it part of the QA suite

Making the plugin available

We now know how to build a plugin, we know how to test it,

we don’t know how to make it available to other projects!

We want something like:

plugins {

id("our.plugin.id") version "our.plugin.version"

}

To do so, we need to ship our plugin to the Gradle plugin portal

Gradle provides a plugin publishing plugin to simplify delivery

…but before, we need to learn how to

-

click $\Rightarrow{}$ pick a version number $\Leftarrow{}$ click

-

click $\Rightarrow{}$ select a software license! $\Leftarrow{}$ click

Setting a version

The project version can be specified in Gradle by simply setting the version property of the project:

version = "0.1.0"

- Drawback: manual management!

It would be better to rely on the underlying DVCS

to compute a Semantic Versioning compatible version!

DVCS-based Automatic semantic versioning

There are a number of plugins that do so

including one I’ve developed

Minimal configuration:

plugins {

id ("org.danilopianini.git-sensitive-semantic-versioning") version "<latest version>"

}

./gradlew printGitSemVer

> Task :printGitSemVer

Version computed by GitSemVer: 0.1.0-archeo+cf5b4c0

Another possibility is writing a plugin yourself

But at the moment we are stuck: we don’t know yet how to expose plugins to other builds

Selecting a license

There’s not really much I want to protect in this example, so I’m going to pick one of the most open licenses: MIT (BSD would have been a good alternative)

- Create a LICENSE file

- Copy the text from the MIT license

- If needed, edit details

Copyright 2020 Danilo Pianini

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated

documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation

the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to

permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

The above copyright notice and this permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the

Software.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS

OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR

OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

Maven-style packaging

JVM artifacts are normally shipped in form of jar archives

the de-facto convention is inherited from Maven:

- Each distribution has a groupId, an artifactId, and a version

- e.g.

com.google.guava:guava:29.0-jre- groupId:

com.google.guava - artifactId:

guava - version:

29.0-jre

- groupId:

- e.g.